As part of my resolution to "see more movies," Peevil and I went to "Volver" last night at the Princess Cinema (Peevil and I also have a resolution to "see more of each other," so we both bought memberships, and now we can't come up with excuses).

I've loved Pedro Almodovar's films since my first exposure -- I think it was "Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down." I miss the raunchy, silly campiness of his older films in the same way that I miss John Waters' old-time craziness...but unlike Waters, Almodovar has mellowed into something beautiful and strange. He's no longer making movies about nuns on LSD, but he's not making blockbusters either. His films are as crazy as ever, really...but he's learned to relax. I think I've finally learned to relax with him.

As always, Volver stars unconventionally beautiful women (Lola Duenas is the logical, toned-down follow up to Rossy de Palma's "pretty but shouldn't really be" standards...far prettier than Penelope Cruz anyday). These women -- as always -- work towards gaining independence from men and towards friendship with each other. Crazy stuff happens and everybody stands around and acts like it's sort of normal. Almodovar stalwarts Carmen Maura and Chus Lampreave (she'll always be Sister Rat to me!) are just so darn GOOD and so darn SPECIAL that it makes my heart ache.

The plot? Well, Peevil and I had already figured out the two big twists halfway through, but we still enjoyed the development. You tend to know what Almodovar's up to, but you never know how he'll present it. I also notice that when you watch his films in a crowd, people don't know whether they're supposed to laugh or not. Sadly the two old ladies behind me decided to live on the edge and laugh at everything, and they were sorely in need of a pepsodent soak. Peevil didn't notice because she had her nose buried in her coat; the theatre was freezing.

Anyway: go into Volver expecting an intriguing, funny, harrowing story about Spanish women with curvy bums. That way you'll get what you want and you won't be disappointed.

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

Traumatizing the Cat

I've had Zsa Zsa for six years and I've never taken her to the vet. I know several people who never take their cats for regular check-ups, and since Zsa Zsa is as healthy as a pony I figured there was no point.

I've had Zsa Zsa for six years and I've never taken her to the vet. I know several people who never take their cats for regular check-ups, and since Zsa Zsa is as healthy as a pony I figured there was no point.But guilt finally won out. Also I bought her one of those cat water fountains, which is sort of like buying a Thunderbird fountain for an alcoholic. She's always been OBSESSED with running water, and now she can drink it whenever she wants...and as a result her litter box is a wet swampy mess.

Golly! Maybe she's diabetic? Maybe she caught it from me that time I smooched her?

So I made an appointment at the vet's, dusted off her old cat carrier, and dragged poor Zsa Zsa into a strange environment. She meowed pitifully in the cab when I got out to get her adoption papers. She sat with her face pressed against the grille, gazing at me, in the back seat. Then, at the vet's office, she had a staring contest with a dog (and won), she hissed and growled when the vet examined her butt, and finally she looked resigned and proud as they wrapped her in a blanket and took her away to do a biopsy of That Thing On Her Head.

First things first: she's probably not diabetic. Rather than subject her to blood work they gave me a packet of litterbox crystals that supposedly change colour when she pees on them.

Next, That Thing On Her Head. It's a lump that suddenly grew during her first year with me but hasn't changed since. Turns out it's a mastocytoma (warning, sad and gross), which in a dog is critical...but cats get them frequently and they are almost always benign.

Finally, her "happy-twitching." When she's very very relaxed and I'm petting her, her face starts to spasm slightly; her lips twich suddenly, her mouth wiggles a bit, her eyes clench spastically. It never seems to bother her but looks like some kind of seizure. I mentioned it to the vet because I noticed she was doing it in the clinic, which means it happens when she's both happy AND stressed. I'd be stressed too if the vet thought MY name was pronounced "Saw-see."

The vet was very happy to expound on twitching cats. She's heard this from a few other cat owners and she feels it's a "cluster seizure," but since nobody has the time, motivation, or money to stick cats in MRI scans to see how they act when they're happy...well, maybe we'll never know what it's all about.

A non-deductable $70 later, I now have peace of mind and Zsa Zsa -- on my lap as I write this -- doesn't appear permanently damaged. Of course I still have to do the urine test...but I'll leave that for another day. Jeez, I think I found the whole experience more stressful than she did.

Saturday, January 27, 2007

Palatable Bollywood Joy: Maghta Hai Kya

If I were going to pick one clip that embodied the best of Bollywood -- a clip palatable to non-fans AND avoiding outright culture-shock goofiness -- I'd pick this scene from the film "Rangeela."

What you've got here (by way of plot) is sweet bumpkin Aamir Khan trying to deal with the sudden stardom of his girlfriend, Urmila Matondkar. This song (Maghta Hai Kya) is just showing us their passion, love, unpretentious silliness, and adventurous spirit...before they begin to drift apart into different classes and ambitions.

Why's it special? First off it's a great song by unconventional musician A. R. Rahman, known for his odd rhythm, studio trickery, and long quiet stretches broken by sudden and unexpected shocks. You've also got Ram Gopal Varma directing, who at the time (1996?) considered himself the "Steven Spielberg of Bollywood," which in this case was a good thing. Finally you've got Urmilla and Aamir who had a great chemistry and a certain charm (this was during their pre-fame days...in fact, this was the film that really "made them.")

Also notable is this was when the "kiss taboo" in Indian films began to loosen: note the strange "kiss-and-cut" moment halfway through. And there's a green-screen effect that sort of works. And leaf-covered natives. And sexiness. And sweetness. You can almost excuse the traditional "standing on rocks and pinwheeling" elements near the beginning, which any fan of Bollywood has seen far too much of.

The choreography, though more adventurous than average, is still typical Bollywood: it doesn't matter if it makes sense in a cultural or traditional way, just as long as it LOOKS GOOD. Even when it doesn't. Which sums up the fun of Bollywood in general.

So in short: it's moments (and movies) like this that really MADE Bollywood for me, when I watched it regularly. Eventually I got tired of seeing the same things over and over again, and also got jaded with the craziness, but some films really shone, and "Rangeela" was one of them.

What you've got here (by way of plot) is sweet bumpkin Aamir Khan trying to deal with the sudden stardom of his girlfriend, Urmila Matondkar. This song (Maghta Hai Kya) is just showing us their passion, love, unpretentious silliness, and adventurous spirit...before they begin to drift apart into different classes and ambitions.

Why's it special? First off it's a great song by unconventional musician A. R. Rahman, known for his odd rhythm, studio trickery, and long quiet stretches broken by sudden and unexpected shocks. You've also got Ram Gopal Varma directing, who at the time (1996?) considered himself the "Steven Spielberg of Bollywood," which in this case was a good thing. Finally you've got Urmilla and Aamir who had a great chemistry and a certain charm (this was during their pre-fame days...in fact, this was the film that really "made them.")

Also notable is this was when the "kiss taboo" in Indian films began to loosen: note the strange "kiss-and-cut" moment halfway through. And there's a green-screen effect that sort of works. And leaf-covered natives. And sexiness. And sweetness. You can almost excuse the traditional "standing on rocks and pinwheeling" elements near the beginning, which any fan of Bollywood has seen far too much of.

The choreography, though more adventurous than average, is still typical Bollywood: it doesn't matter if it makes sense in a cultural or traditional way, just as long as it LOOKS GOOD. Even when it doesn't. Which sums up the fun of Bollywood in general.

So in short: it's moments (and movies) like this that really MADE Bollywood for me, when I watched it regularly. Eventually I got tired of seeing the same things over and over again, and also got jaded with the craziness, but some films really shone, and "Rangeela" was one of them.

My New Digs: The Shoe-Eating Porch

Sarah Jane Smith

I figured: okay, I just spent a great night in Guelph with wonderful people at a wonderful party...I can go home and enjoy a totally nerdy persuit, right?

So I watched the pilot episode of the "Sarah Jane Adventures."

Gah! Okay, it's a show aimed at pre-teens. Obviously. But those of you (like me) who grew up watching Sarah Jane Smith in the late '70s during the heyday of "Doctor Who" can't help feeling a little nostalgic about her. Or in this case, a LOT nostalgic.

The Sarah Jane character got unceremoniously dumped in 1976, the way many of the Doctor Who "companions" got dumped when things just weren't working out. Elizabeth Sladen (the actress) felt that the character wasn't going anywhere, and she was right...there's only so many times you can say "Doctor, WHAT'S HAPPENING?!?" before things get a little tiresome.

But the problem is, Elizabeth Sladen never went anywhere afterwards. She'd been typecast. And we all loved her and wished we could see her again (though I admit that Leela and Romana kicked butt as travelling companions afterward).

On the heels of her brief return during the second season of the new Doctor Who, introducing a whole new set of neuroses, Elizabeth Sladen stars in her own TV series -- "The Sarah Jane Adventures" -- which is really darn fun. I mean sure, I'm twice the age of the target demographic, but that doesn't matter: Elizabeth Sladen has aged beautifully, she's got a killer pair of boots, and the production team does a great job aiming at children while still being fun for adults.

Besides whatever entertainment value the program has, it makes me happy to see Elizabeth Sladen back on screen again. She has justified her talent, she's a great actress, and if the only way she can prove it is by playing the same character again...well, sad but okay. And need I mention John Leeson as K9?

Okay, okay, the core of this post is the little kid in me screaming "YAY! K9 AND SARAH JANE! AND THEY'RE GREAT!" Nothing else matters. Tomorrow, life goes on.

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

Rising Up and Rising Down (Volume III)

For the last month or so I've been quickly -- but diligently -- making my way through William T. Vollmann's seven-volume opus, "Rising Up and Rising Down." It's an analysis of justifications for defense, looked at from many different angles and since the beginning of recorded history. Now that I'm midway through the third volume -- and almost at the spot where I gave up the last time -- I guess I can say a few things about this beautiful and maddening work.

Vollmann spent twenty years writing this, and it shows. The research is meticulous and his depth of understanding for so many topics is probably unmatched. At the same time, and in an attempt at making his analyses as comprehensive as possible, it can be difficult to follow the convoluted path of his thinking: he justifies carefully thought-out positions, then destroys them, then rebuilds them with new caveats and conditions that are sometimes surprisingly logical and elegant, but at other times totally useless. And he's the first one to tell you when he fails to come up with a practical section in his "moral calculus."

Rather than try to do this book justice, here are a few pointers to anybody considering tackling it (I understand the complete set is long out of print, but there's a "condensed" version available now).

The first volume is difficult to get into. It begins with "Three Meditations on Death" which don't have much to do with the book itself; this is typical of Vollmann, he seems to have trouble beginning his books, so the first chunk tends to be "warming up to the topic," a sort of mental purge so he can get to business. The following two sections show another annoying Vollmann trait: they're essential, but he's given them esoteric titles that only serve to throw the reader off the trail. "The Days of the Niblungs" is an advanced apology about how difficult the book will be to read and how subjective much of it needs to be.

The next ridiculously-titled-but-hugely-important section is "Definitions for Lonely Atoms." Since much of the book is about complex issues generally tackled by groups of people acting against other groups of people, this section is simply an analysis of the rights of the INDIVIDUAL; what are a person's basic offensive and defensive rights? He gets somewhat sidetracked on the issue of weaponry but I think Vollmann scores with his conclusions, which he reaches by analyzing countless historical precedents and by imagining the beginning of the human social contract:

All of these points (and all other points I might reference here) are usually qualified with caveats -- for instance, point 3 specifies that suicide is permissible whenever uncoerced, but most noble as an act of assertion in defense of a right.

The next 3 volumes explore various types of self-defense, and try to codify when self-defense is justified. This is done by carefully defining the terms involved (for example, "inner honor" versus "outer honor"), giving huge amounts of historical detail as case studies, giving continuums of opinion on the subject from the writings of others, and -- most importantly -- defining a set of rules and conditions which make a particularly type of self-defense justified or unjustified.

I've worked my way through his analyses of violent defense of honor (the first, longest, and most complex topic), class, authority, race & culture, creed, war aims, homeland, ground, the earth, and animals. Each section is slightly different in its approach; some are more anectodal (Vollmann's experiences in Bosnia, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Nunuvut), others are careful retellings of historical events (the American Civil War, the Russian Revolution, Napoleon, Caesar vs. Pompey, Joan of Arc, World War One and Two), and others rely a lot on personal interviews with today's activists.

I find the chapters on defense of Earth and defense of animals to be most interesting, because it's there where Vollmann really struggles. In most cases (so far) he's tackled issues that have been explored for centuries and experimented upon by other grand civilizations, but when it comes to Eco-terrorism or the Animal Liberation Front, not only are they relatively NEW (and as yet relatively undefined) issues, but the violent actions tend to be perpetrated by people who seem to be acting on compassionate grounds (never mind that they don't necessarily have compassion for their opponents, but the PETA folks certainly seem to care more for animals than -- for example -- Trotsky seemed to care for the proles).

In his chapter on defense of Earth -- involving the spiking of trees to prevent logging, and any sort of violent uprising to prevent pollution or global warming -- he constructs an elaborate and clever concept: a private army called "Same Day Liberations." It sounds great until you begin to realize that Vollmann is REALLY wallowing in despair; he knows the idea won't work. People are too easily bought off, disinformation is too easily spread by rich and powerful authorities, human beings are too short-sighted. All he can really suggest is that we become our own experts and be critical of where our information comes from.

The most interesting point he raises, though, is Garrett Hardin's "Tragedy of the commons," which is so depressing that I'll just quote Vollmann's paraphrase:

When it comes to defense of animals, Vollmann is even more uncertain, mainly because nobody can settle on a threshold at which violence against animals must stop (monkeys, dogs, rabbits, mice, flies, flatworms, bacteria?), and how useful violence against animals actually is (medical research, hunter/gathering societies, animal attacks, community rituals).

Vollmann is never more interesting than when he's writing about the Inuit, as far as I'm concern. He's the first to say that he is perhaps unreasonably romantic about their lifestyle, but his descriptions of seal hunts -- and subsequent family dinners of raw frozen meat -- are eye-opening. When an animal-rights activists tells him that the Inuit would stop hunting for meat if they were provided with enough other types of food (disregarding the cost of getting the food to them, since agriculture just isn't feasible up there), he delivers a stunning comparison: this is exactly what Cortes said about the Aztecs, it's the placement of one group's ethos over another's, and the disgusting assumption that the other group will gleefully embrace your own values because they're naturally "better."

My favourite moment, though, is when Vollmann spends several pages writing about how wonderful his sealskin kamiks (moccasins) are, how important they've been to him in his travels up north, and how synthetic boots can't match his kamiks in certain situations. After waxing romantic about his kamiks for four pages gives an animal activist named Lizzy her own chapter to respond. She says simply:

Vollmann spent twenty years writing this, and it shows. The research is meticulous and his depth of understanding for so many topics is probably unmatched. At the same time, and in an attempt at making his analyses as comprehensive as possible, it can be difficult to follow the convoluted path of his thinking: he justifies carefully thought-out positions, then destroys them, then rebuilds them with new caveats and conditions that are sometimes surprisingly logical and elegant, but at other times totally useless. And he's the first one to tell you when he fails to come up with a practical section in his "moral calculus."

Rather than try to do this book justice, here are a few pointers to anybody considering tackling it (I understand the complete set is long out of print, but there's a "condensed" version available now).

The first volume is difficult to get into. It begins with "Three Meditations on Death" which don't have much to do with the book itself; this is typical of Vollmann, he seems to have trouble beginning his books, so the first chunk tends to be "warming up to the topic," a sort of mental purge so he can get to business. The following two sections show another annoying Vollmann trait: they're essential, but he's given them esoteric titles that only serve to throw the reader off the trail. "The Days of the Niblungs" is an advanced apology about how difficult the book will be to read and how subjective much of it needs to be.

The next ridiculously-titled-but-hugely-important section is "Definitions for Lonely Atoms." Since much of the book is about complex issues generally tackled by groups of people acting against other groups of people, this section is simply an analysis of the rights of the INDIVIDUAL; what are a person's basic offensive and defensive rights? He gets somewhat sidetracked on the issue of weaponry but I think Vollmann scores with his conclusions, which he reaches by analyzing countless historical precedents and by imagining the beginning of the human social contract:

- To violently defend yourself, or not.

- To violently defend another, or not.

- To destroy yourself or preserve yourself.

- To violently destroy another who would be better off dead

- To violently defend your property, or not.

All of these points (and all other points I might reference here) are usually qualified with caveats -- for instance, point 3 specifies that suicide is permissible whenever uncoerced, but most noble as an act of assertion in defense of a right.

The next 3 volumes explore various types of self-defense, and try to codify when self-defense is justified. This is done by carefully defining the terms involved (for example, "inner honor" versus "outer honor"), giving huge amounts of historical detail as case studies, giving continuums of opinion on the subject from the writings of others, and -- most importantly -- defining a set of rules and conditions which make a particularly type of self-defense justified or unjustified.

I've worked my way through his analyses of violent defense of honor (the first, longest, and most complex topic), class, authority, race & culture, creed, war aims, homeland, ground, the earth, and animals. Each section is slightly different in its approach; some are more anectodal (Vollmann's experiences in Bosnia, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Nunuvut), others are careful retellings of historical events (the American Civil War, the Russian Revolution, Napoleon, Caesar vs. Pompey, Joan of Arc, World War One and Two), and others rely a lot on personal interviews with today's activists.

I find the chapters on defense of Earth and defense of animals to be most interesting, because it's there where Vollmann really struggles. In most cases (so far) he's tackled issues that have been explored for centuries and experimented upon by other grand civilizations, but when it comes to Eco-terrorism or the Animal Liberation Front, not only are they relatively NEW (and as yet relatively undefined) issues, but the violent actions tend to be perpetrated by people who seem to be acting on compassionate grounds (never mind that they don't necessarily have compassion for their opponents, but the PETA folks certainly seem to care more for animals than -- for example -- Trotsky seemed to care for the proles).

In his chapter on defense of Earth -- involving the spiking of trees to prevent logging, and any sort of violent uprising to prevent pollution or global warming -- he constructs an elaborate and clever concept: a private army called "Same Day Liberations." It sounds great until you begin to realize that Vollmann is REALLY wallowing in despair; he knows the idea won't work. People are too easily bought off, disinformation is too easily spread by rich and powerful authorities, human beings are too short-sighted. All he can really suggest is that we become our own experts and be critical of where our information comes from.

The most interesting point he raises, though, is Garrett Hardin's "Tragedy of the commons," which is so depressing that I'll just quote Vollmann's paraphrase:

Problem: What is my utility in adding one more animal to my herd on a common pasture?On a related note he mentions what he calls "The Crocodile's Maxim," which boils down to a general way of thinking that things MUST get better/bigger/easier, and if they don't then we're doing something wrong. But it's unlikely that things can increase in this way indefinitely; how many people can the earth support? How big can a company get? I think this is a very important and awful part of human nature and I wish I could express it better. Every time I see a report that a company is achieving record stock prices, I think jeez, how can anybody believe that will continue forever, and what's wrong with a stock staying at the same price (I know what a stockholder would say, at least).

Solution: Buy another animal, let it overgrazed, and be damned to everybody else

When it comes to defense of animals, Vollmann is even more uncertain, mainly because nobody can settle on a threshold at which violence against animals must stop (monkeys, dogs, rabbits, mice, flies, flatworms, bacteria?), and how useful violence against animals actually is (medical research, hunter/gathering societies, animal attacks, community rituals).

Vollmann is never more interesting than when he's writing about the Inuit, as far as I'm concern. He's the first to say that he is perhaps unreasonably romantic about their lifestyle, but his descriptions of seal hunts -- and subsequent family dinners of raw frozen meat -- are eye-opening. When an animal-rights activists tells him that the Inuit would stop hunting for meat if they were provided with enough other types of food (disregarding the cost of getting the food to them, since agriculture just isn't feasible up there), he delivers a stunning comparison: this is exactly what Cortes said about the Aztecs, it's the placement of one group's ethos over another's, and the disgusting assumption that the other group will gleefully embrace your own values because they're naturally "better."

My favourite moment, though, is when Vollmann spends several pages writing about how wonderful his sealskin kamiks (moccasins) are, how important they've been to him in his travels up north, and how synthetic boots can't match his kamiks in certain situations. After waxing romantic about his kamiks for four pages gives an animal activist named Lizzy her own chapter to respond. She says simply:

"I just wonder how that seal felt when he was killed so some guy could take his skin and go up to the Magnetic Pole to think."

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

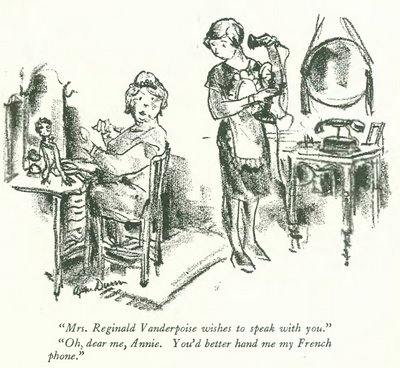

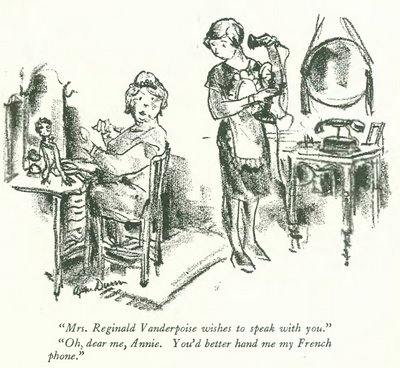

The "French Phone"

In early 1927, the New Yorker begins mentioning a revolutionary telephone that everybody wants to have. Called "The French Phone," I didn't know what the heck it was until I ran across this cartoon this morning:

It seems this type of phone -- with the receiver and headset combined into one section, the way we know it today -- cost more to install and caused minor havoc with the Bell Telephone company.

It seems this type of phone -- with the receiver and headset combined into one section, the way we know it today -- cost more to install and caused minor havoc with the Bell Telephone company.

To get around the higher cost, people bought cheaper French Phones made by third-party companies and installed them personally. But Bell had a contract in its clause that nobody had paid attention to previously: you were not allowed to use non-Bell accessories with Bell's telephone service.

From the sounds of it, this prohibition was pretty much unenforcable. It may have begun the breakdown of Bell's phone-and-service monopoly. If you're interested in learning more about early telephones, check out this site. But I warn you: you'll suffer a disturbing MIDI loop of "Puttin' On the Ritz."

PS: Why was it called "The French Phone?" Apparently it resembled phones in Europe. What that means exactly I'm not sure.

It seems this type of phone -- with the receiver and headset combined into one section, the way we know it today -- cost more to install and caused minor havoc with the Bell Telephone company.

It seems this type of phone -- with the receiver and headset combined into one section, the way we know it today -- cost more to install and caused minor havoc with the Bell Telephone company.To get around the higher cost, people bought cheaper French Phones made by third-party companies and installed them personally. But Bell had a contract in its clause that nobody had paid attention to previously: you were not allowed to use non-Bell accessories with Bell's telephone service.

From the sounds of it, this prohibition was pretty much unenforcable. It may have begun the breakdown of Bell's phone-and-service monopoly. If you're interested in learning more about early telephones, check out this site. But I warn you: you'll suffer a disturbing MIDI loop of "Puttin' On the Ritz."

PS: Why was it called "The French Phone?" Apparently it resembled phones in Europe. What that means exactly I'm not sure.

Sunday, January 14, 2007

If the Nightingale / Could Sing Like You...

I just finished rewatching the Marx Brothers in "Monkey Business," you know, the one where they're stowaways and need to impersonate famous people to get off the boat. Errr, to differentiate it from "A Night at the Opera," this is the one where they pretend to be Maurice Chevalier, and where Harpo does a Punch & Judy gag with a lot of children who are being forced to laugh. And you know how awful it is when little kids have to pretend to laugh in a film.

I just finished rewatching the Marx Brothers in "Monkey Business," you know, the one where they're stowaways and need to impersonate famous people to get off the boat. Errr, to differentiate it from "A Night at the Opera," this is the one where they pretend to be Maurice Chevalier, and where Harpo does a Punch & Judy gag with a lot of children who are being forced to laugh. And you know how awful it is when little kids have to pretend to laugh in a film.Some of the best moments in a Marx Brothers movie are when Chico does a one-on-one routine with either Harpo or Groucho:

GROUCHO: Well, the picnic's off, we didn't bring any red ants.

CHICO: I know some Indians got a couple of red aunts.

I also love to watch the Marxes tease and confuse women. I don't know whether it's a misogynistic streak or what, but a common thread in these movies is one of the brothers flirting with a woman, routinely insulting her at the same time, and then scaring the heck out of her or sort of physically assaulting her. I find this refreshing not because I like to see women get insulted, jacked up like cars, or crushed under couch cushions, but because I like to see a Hollywood "flirtation routine" get turned completely on its head.

CHICO: You're a very pretty girl. You've got "it."

MANICURIST: Thank you.

CHICO: And you can keep it.

Watching Groucho irrationally insult a pretty girl ("Does your husband know you used to dance in a flea circus?") also provides a welcome change from hatchet-faced Zeppo woodenly wooing the dull romantic lead. And anything that delays a harp solo is a good thing in my books.

(Every blog entry requires a certain amount of writing-agony, but this time around I couldn't remember how to spell cushion...think about it, it's a strange word)

My New Digs: Satan's Lazy Susan

Ladies and gentlement, let me present: Satan's Lazy Susan.

Ladies and gentlement, let me present: Satan's Lazy Susan.What you're seeing is the sanitized version. When I first opened this cupboard I almost vomited, and that ain't no lie. Besides being coated with a thick layer of mouse feces, all three shelves of Satan's Lazy Susan were also covered with rotten food and other unidentifiable substances. And there was an old bottle of vanilla extract in there somewhere.

My first instinct was to nail the cupboard shut and never think about it again, but I knew that was impossible. How could I actually WASH DISHES under such an abomination? So I put on the rubber gloves -- and gave some credit to whoever decided to BUILD this crazy thing -- and spent an hour spraying, digging, sweeping, and gagging.

Now I have a clean lazy susan which I'll never use. I admit it has a "Leave it to Beaver" appeal, but whenever I look at it I think of the words "Totally F*cking Disgusting."

Such is the joy of moving into an old apartment. You never know what you'll find.

Saturday, January 13, 2007

The Horrible Hagfish

Yesterday I brought you the bread-secreting bowery bums. Today I bring you...the slime-secreting hagfish!

Yesterday I brought you the bread-secreting bowery bums. Today I bring you...the slime-secreting hagfish!I love to read about disgusting animals, especially parasites. It instills in me a sense of nature's ingenuity and her unique code of aesthetics: lots of animals are horrible, but some of the most horrible animals are also the best adapted to their environment. Sometimes I feel like those pre-1930s naturalists who considered such animals to be degenerate abominations, and wrote treatises about how they had actual "devolved" due to laziness and immorality. Other times I can only marvel at their functional beauty.

I also like to read about horrible animals because I like to be grossed out.

So I happily present the hagfish. They're usually about 18 inches long and, like a lamprey, they can attach themselves to other fish and slowly eat them alive. But unlike the lamprey, the hagfish has a special ability to tie itself in knots...this ability gives it traction, allowing it to actually INSERT itself into other fish...and eat them from the inside out.

Hagfish can also produce HUGE amounts of fibrous slime...they can literally cocoon themselves in slime in just a few seconds, and can clean themselves off again by tying their bodies into a knot and slipping the knot back along their skin. Here's a video of a hagfish inside a slime cocoon...you can see it best halfway through.

WARNING: According to this link hagfish sometimes "burrow in the soft bottom." So if you've been feeling strange lately, grab a mirror and take a look. You don't want somebody ELSE to tell you.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)